Ken MacLeod's comments.

The title comes from two quotes:

“If these are the early days of a better nation, there must be hope, and a hope of peace is as good as any, and far better than a hollow hoarding greed or the dry lies of an aweless god.”—Graydon Saunders

Contact: kenneth dot m dot macleod at gmail dot com Blog-related emails may be quoted unless you ask otherwise.

Emergency Links

British Red Cross

Disasters Emergency Committee

UNICEF

Hurricane Relief

American Friends Service Committee

LINKS

Self-promotion

Buy my books

Buy signed copies!

Follow me on Twitter!

The Human Genre Project

The Human Genre Project

Comrades and friends

Charlie Stross

Martin Wisse

Making Light

Avedon Carol

The Pagan Prattle

Cheryl's Mewsings

Farah Mendlesohn

Bridesmaid

Svein Olav Nyberg's old blog

Svein Olav Nyberg's new blog

Alister Black

Kevin Williamson

Alan Freeman

Kathryn Cramer

MaxSpeak

Jim Henley

John Baker

Nicholas Whyte

The Sharp Side

Barbaric Document

The Woolamaloo Gazette

Kevin Carson

Thomas Knapp

Arthur Silber

Grand Hotel Abyss

Devizes Melting Pot

A Finer World

Austro-Athenian Empire

The Art of the Possible

Cupcake Couture

Brian Micklethwait

Diane Hannover

TJ's Place

Mat Coward

Iain Fraser Grigor

Gail Wendorf

ubiquitous surveillance

Dubious Prospects

Ilorien

Sharon King

Kristine Lowe

Rich Puchalsky

Lamontations

Cory Doctorow

Parallel Futures

Lord Dunderheid

Colleagues

Genomics Forum

Genotype

Forum Tweets

the write reality

Pippa Goldschmidt

My Forum page

Sociology, Genomics and SF

EUSci

The University of Edinburgh

Genomics

What Is Genomics?

What is Synthetic Biology?

SynBioStandards

Genetic Future

Genetic Inference

Action Bioscience

Cardiff sciSCREEN

Genomic Minds

The Fourth Domain

Edinburgh

Guardian Edinburgh blog

The Edinburgh Reporter

City of Literature Trust

Textualities

Writers Bloc

Word Power

Transreal

McShandy's

Forest Publications

The Forest Cafe

Avalanche Records

Scottish Knife Collection

Sea Kist

Joyce Paton

Chris Koujou

Author Portraits

Luath Press

Tychy

Dig-In Bruntsfield

Writers Blog

SF Writers' blogs

Dead by Dawn

Forbidden Planet

Ian McDonald

The Mumpsimus

Dr Ian Hocking

Barbaric Document

Mundane SF

Justina Robson

Neal Asher

Michael Rosen

Warren Ellis

John Scalzi

Sean Williams

Jack Deighton

Rudy Rucker

Glenda Larke

Alan Campbell

Gavin Inglis

Hannu Rajaniemi

Lou Anders

Nick Harkaway

Paul McAuley

Lois McMaster Bujold

LabLit

M. John Harrison

Kelley Swain

Robert J. Sawyer

Will Shetterly

Stefan Pearson

aiko writes: poems

The Lost Book

The Trease Project

Peter Watts

Karla Schmidt

Deborah J Miller

Juliet E McKenna

Mike Cobley

Philip Palmer

Nick Wood

Catherynne M. Valente

Gail Carriger

Liz Williams

Morag Edward

Adam Roberts

Jo Walton

Nicola Griffith

Alastair Reynolds

Kari Sperring

Alan Bissett

My Writing Life

Helen Jackson

Caroline von Schmalensee

N. K. Jemisin

Cici James

Joan Slonczewski

Gwyneth Jones

Michael Rosen

Ryan Van Winkle

C.J. Cherryh

Russell Jones

Georgina Bruce

Katrina Leno

Claire Askew

Steven Brust

Mary Robinette Kowal

Regi Claire

Ron Butlin

Ruth Sabath Rosenthal

Jaine Fenn

Nnedi Okorafor

Editor Blogs

John Jarrold

Publisher Blogs

Tim Holman

Brother Blogs

MacLeod Cartoons

Skiffy

Ansible

Redstone SF

Futurismic

SciFiDimensions

io9

Tor.com

Pyr

Orbit

PS Publishing

Feminist SF

World SF News

Biology in SF

Raritania

Steampunk Fashion

Torque Control

Post-Weird Thoughts

Ivor W. Hartmann

StarShipSofa

Star Wars Modern

The Outer Alliance

Eve's Alexandria

Beyond Victoriana

Strange Horizons

Salon Futura

Afrocyberpunk

pornokitsch

SciFi Ideas

Three, If By Robots

Brits Blog

The Sharpener

The Register

Velvet Glove, Iron Fist

Blood and Treasure

The Gaping Silence

The Yorkshire Ranter

Excuse Me Whilst I Step Outside

' ... a treeless, flowerless land, formed out of the refuse of the Universe, and inhabited by the very bastards of Creation'

Socialism First!

Red Paper

Aye We Can!

Bella Caledonia

Scottish Roundup

Scottish Politics

SSP

Solidarity

Scottish Left Review

Democratic Left Scotland

Between the Hammer and the Anvil

SNP Tactical Voting

A Place to Stand

Freedom and Whisky

Independence

Gerry Hassan

Better Nation

Bright Green Scotland

Caledonian Mercury

Lallands Peat Worrier

Lesley Riddoch

Clyde Space

Spaceport Scotland

Land Matters

Scottish Review

Scottish Review of Books

The Firm

STV Local

Frontiers

Whitehall 1212

Ian Smart

Notes from North Britain

Amazing Things

Astronomy Picture of the Day

Hubble Telescope

Fragile Oasis

Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy

Dictionary of the History of Ideas

Internet SF DataBase

Arts and Letters Daily

3 Quarks

1911 Britannica

Wikipedia

BBC

Daily Mash

Fortean Times

BoingBoing

Three-Toed Sloth

James P. Hogan

MemeMachineGo!

small WORLD

Derelict London

Good News

Strange Maps

The Simulation Argument

Better Living Through Chemistry

Poems on the Book of Life

The Periodic Table of Science Fiction

RAW Illumination

The Realist Archive

The New Atlantis

Faith

Flat Earth

Fixed Earth

Geocentricity

6 ky Earth

10 ky Earth

4.5 Gy Earth

Creation Wiki

Sacred Texts

The Brick Testament

The LOLcat Bible

Reason

New Humanist

Edinburgh University Humanist Society

WTA

IEET

Cyborg Democracy

Nick Bostrom

Bad Astronomy

WorldChanging

Cosmic Variance

Sean Carrol

Bruce Schneier

i-studies

The Eternal Golden Braid

The Secular Web

NSS

Richard Carrier

Russell Blackford

Conscious Entities

David Chalmers

the Edge

Naturalism.Org

Talk Reason

Stephen Law

Science after sunclipse

The Threat to Reason

Atheists of Silicon Valley

Blag Hag

Rationally Speaking

Bad Science

Enemies of Reason

Tabloid Watch

Daily Mail Watch

Perpetual Motion

Skepticblog

This is What a Scientist Looks Like

Freethought Blogs

Crooked Timber

Kenan Malik

Atheism: Proving the Negative

Stoicism Today

Sense about Science

Evolution

Why Evolution is True

The Panda's Thumb

Pharyngula (SciB)

Pharyngula (FtB)

RichardDawkins.net

The Voyage of HMS Beagle

Evolving Thoughts

The Lancelet

Pleiotropy

The Digital Cuttlefish

Glenn Morton's Pages

Talk.Origins

Creation Science and Earth History

Creation 'Science' Debunked

ASA

The GeoChristian

NCSE

BCSE

Oolon Colluphid's Guide to Creation

Recovering YECs

Beyond the Firmament

Highly Allochthonous

Caught in a Bad Project

Playing Chess with Pigeons

Shit You Didn't Know About Biology

War and Revolution

Antiwar.com

Lenin's Tomb

Empire Burlesque

CounterPunch

World Socialist Web Site

British Army Rumour Service

Circling the Lion's Den

International Crisis Group

Baghdad Burning (Riverbend)

Iraq Today

Left I on the News

Informed Comment

Informed Comment Global

Tom Dispatch

It's No Accident

Empire Notes

the eXile

The Exiled

Inanities

Matt Carr's Infernal Machine

MidEast Shuffle

The Duck of Minerva

In the Mind Field

Mutualist Militants

Free Market Anti-Capitalism

Larry Gambone

Red Lion Press

crispin sartwell

In the Libertarian Labyrinth

Liberty Alone

Rad Geek People's Daily

Propaganda Lalaland

Markets Not Capitalism

Democratic Socialists

Scottish Labour

Tom Harris MP

Bob Piper

LabourList

Socialist Party, USA

Socialist Webzine

Chartist

Appeal to Reason

Labour and Capital

Left Futures

grimmerupnorth

The Bickerstaffe Record

The Socialist International

Labour Lords

Scarlet Standard

Shifting Grounds

Renewal

Impossibilists and Ilk

SLP

SPGB

Socialist Studies

Socialism or Your Money Back

Inveresk Street Ingrate

Vaux Populi

Mission

Timid Maximalist

Class Warfare

Reasons to be Impossible

Mailstrom

Ragged Trousered Philanthropist

Wobbly Times

Viva La Quarta

International Viewpoint

In Defence of Marxism

SWP

Socialist Worker (UK)

Socialist Worker (US)

International Socialism

Socialist Action (US)

CWI

AWL

Anti-SEP-tic

Socialist Action

Communist Parties

CP of Britain

CP of Ireland

CPUSA

CPI(M)

Iraqi CP

CP of Israel

SACP

ML Today

SolidNet

21centurymanifesto

Revolting Europe

L'Humanite in English

Other revolutionaries

CPGB

Worker-communist Party of Iran

the commune

Radical Resources

Housmans Bookshop

Morning Star

Critiques of Libertarianism

Hitler was a Capitalist

Labournet UK

China Labour Review

Marxists Internet Archive

From Marx to Mao

Leninist.biz

Autodidact

Amiel & Melburn Trust

The New Reasoner

Lawrence & Wishart

hegemonics

Marxsite

Marxmail

Marx Myths

Revolutionary History

Monthly Review

What Next?

William Blum

Grover Furr

Bertell Ollman

What's Left

Reality

Paul Cockshott

Critique

The Socialism Web Site

Spectrezine

21st C. Socialism

SolidarityEcon

Left Atomics

Socialist Economic Bulletin

naked capitalism

Thoughts on Economics

Debunking Economics

Research on Money and Finance

Southall Black Sisters

Ancient Communism

Key Trends in Globalisation

Readable Reds

Splintered Sunrise

Soviet Goon Boy

Renegade Eye

Dave's Part

Cedar Lounge

Unrepentant Marxist

Though Cowards Flinch

Mark Steel

Critical Montages

The Curmudgeon

A few words before we go

Stephen Gowans

Liam Mac Uaid

Socialist Unity

Southpaw Punch

Harpy Marx

Madame Miaow

Reading the Maps

Stroppy Blog

A Very Public Sociologist

Tendance Coatsey

Boffy's Blog

Penny Red

Show Biz Red

Stalin's Moustache

Lipstick Socialist

For the sake of the argument

Norman Geras

Sean Gabb

Libertarian Alliance (Official)

Libertarian Alliance (Provisional)

Libertarian Party UK

Spiked Online

Poumista

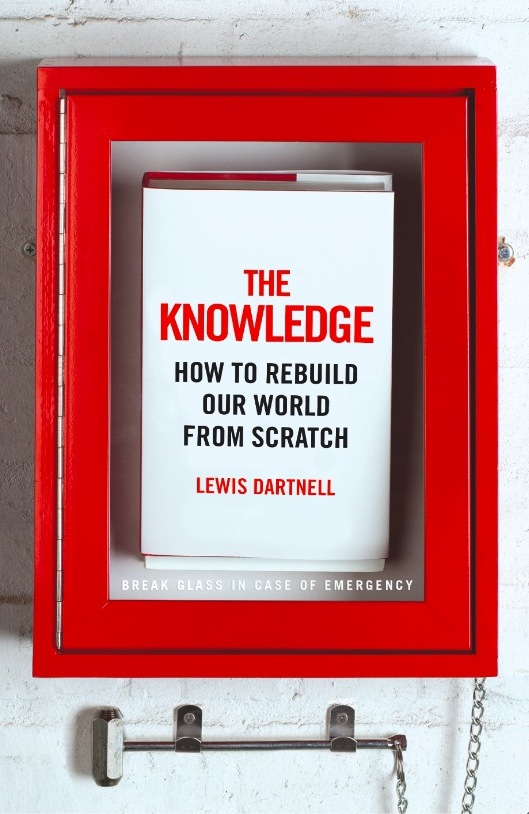

World-Building the Real World

15 Comments:

If it all came crumbling down, I'd personally rather start something different than just rebuild what was. Still, the book does seem worth a read; I'll have to find a copy.

apophasis - that thought had occurred to me :-)

Todd - Dartnell actually does consider how different the post-catastrophe society would have to be.

Whether your vision of the future is a recreation of the glorious past or a new direction, you still have to somehow achieve it. If you think a monastic commune is the way forward from the worldly focus of the former empire, you have to find a location, build shelter, grow food, survive barbarian raids, and, if you want books, make the colours from local rocks and lichens (the latter brilliantly achieved by the maker of the Lindisfarne Gospel, in its way a genius-level feat of chemistry)

ejh - Just an accident of the way I wrote it - usually I copy and paste my draft into the HTML box, this time I pasted into Compose and added the links.

"I didn’t know that a lathe is a sort of von Neumann machine, or that retrieving at least one long-threaded screw from the ruins is crucial."

It isn't crucial, it just helps (or how could they exist now?). The trick for making such screws was actually worked out by the man who designed and had made the tool for cutting the grooves in decent diffraction gratings, whose name I forget but I'm sure people can google, and curiously enough Leo Frankowski picked up on it and put it in one of his "Lord Conrad" novels (though he screwed up with his idea to simplify floor planking by using wider planks so you don't have to cut as many - the wider the planks, the wider the gaps between them have to be to allow for expansion and contraction with varying temperature and humidity, but people can trip over gaps that are too wide). The technique for making a long-threaded screw is simple and straightforward, though it takes a lot of work:-

- Roughly make a long-threaded screw in the form of a bolt by wrapping a wire or cord around a straight rod in a spiral, marking the gaps, and cutting it by hand where marked.

- Make a matching long nut in two C shaped halves by using the bolt to mark its profile, say with engineer's blue, and then similarly cut threading in the halves where marked.

- Put the bolt in the nut with the two halves loosely held together, say with wedges, and start winding the bolt back and forth just a few turns while dripping in a water suspension of coarse abrasive.

- Over several days (much longer, for a diffraction grating) tighten up the wedges and make the abrasive finer.

After all that, the screw profile will have evened itself out uniformly along the whole length, and you'll have finished. A lathe also needs straight line guides, which you can set up with flat plates made by a similar incremental process devised by Whitworth in the nineteenth century. Oh, and if you have a flat plate you can use it to straighten the rod you need by yet another similar incremental process.

Also curiously enough, in his The Isles of Unwisdom Robert Graves recorded a mediaeval superstition arising from a similar bootstrapping problem: smiths could improvise tools to make almost any tool they didn't yet have, but tongs always needed tongs to make them and so a belief arose that God gave the first tongs to the first smith, Tubal Cain. And no, I don't know the way around that problem. Time travel, maybe?

but tongs always needed tongs to make them

Green wood will work to make your first tongs

I am dubious about the basic premise that such a book is needed

My library contains dozens of books about making things

The world is full of people who make things - mostly for fun

I really don't see how you can lose that

Saying that that book sounds fun - I may get an ebook of it

Duncan Cairncross, I would have guessed that you could improvise tongs in some way like that too, but if the superstition based on needing tongs to make tongs was recorded accurately there could have been some problem with that sort of improvising that I don't know.

I've chased up those references I mentioned:-

- The person who worked out the trick for making screws good enough to make high quality diffraction gratings was Henry Augustus Rowland, and he describes his method here.

- Leo Frankowski describes making the screw for a lathe without having a lathe already in The Radiant Warrior thus (but without making it clear that the nut has to be long too):-

"I needed an engine lathe to accurately cut screws and to make good taps and dies. And an engine lathe needs accurate screws to feed the tool along the stock. I had to have a screw to make a screw!

"I laid the problem aside, hoping my subconscious would come up with something, and worked on the rest of the engine.

.

.

.

"But I still hadn't figured out how to make a good screw. Finally, I just drew up a simple engine lathe, even though I didn't see how we could possibly build one. By this time, we had pretty much duplicated the machinery from the brass works at Three Walls, complete with pigs in huge hamster cages turning the lathes, so I gave the drawings to Ilya and told him to make me one.

"Ilya was a good man at a forge, but he didn't have the machining experience of the Krakowski brothers. I gave this difficult project to him because the Krakowski brothers were reasonable enough to ask questions until they understood something, and I didn't have the answers to match their questions.

"Ilya, on the other hand, was never reasonable. His ego was such that he would never admit that there was anything that he didn't quite grasp. He was belligerent, intolerant, and bullheaded, but he wasn't stupid.

"The engine lathe would be the most complicated piece of equipment we owned, but I gave the project to him as casually as if I was asking for an axe head. I simply explained what it did and why, and asked to have it done as soon as possible. He stared at the drawings for a few moments and then said that if I wanted the silly thing, he'd build it.

.

.

.

"At one point I was walking through the plant and saw Ilya carefully wrapping a woman's bright red ribbon around a smooth brass rod, and carefully scribing on the brass where the top of the ribbon came to as he went along. I didn't say a word.

"Another time I saw him deliberately pouring fine sand on a set of running gears, while on another machine one of his assistants was running an iron nut back and forth on a long brass screw. The nut was in two halves and clamped back together, and it too was dusted with fine sand. The assistant said that he had been doing this boring work for two weeks, but I didn't want to get involved. If Ilya somehow did the job, great. If he fell on his ass, the humiliating experience might make him easier to live with.

"But Ilya did it. The engine lathe worked better than I had expected, and Ilya's ego was so monstrous that he wouldn't even accept praise for it. He pretended that he could do that sort of thing every day. So I put him in charge of making the steam-powered sawmills, and told him not to take so long this time."

P M Lawrence,

you could think of the tongs thing as being the same as the bloke who stole fire from the gods. Intrinsically unlikely but a nice story that exalts the objects origins.

This sounds like a good book, I'll have to get a copy.

I think I'll buy an ebook copy. Keep a copy in the cloud in case some disaster strikes, that way I'll always be able to get at it. Oh...

Grrr, that "NASA" study made me mad. I finally found the actual report, stared aghast at the 8 equations you mentioned and raged once again that some people are too easily seduced by Cool Math and forget that their simplistic equations are Stuff That Came Out Of Their Heads, not reality. Sorry. *heavy breathing slows*

Will definitely read the Dartnell book, thanks for the tip. I do hope it doesn't presuppose that there is only one, inevitable way of rebuilding "our world"?

I do hope it doesn't presuppose that there is only one, inevitable way of rebuilding "our world"?

I'm happy to assure you it doesn't.

I hope he remembered to cover brewing and distilling.

By TonyC, at

Friday, March 28, 2014 2:38:00 pm

TonyC, at

Friday, March 28, 2014 2:38:00 pm